Joe Biden will begin leading the US today, January 20th, amid a pandemic, an opioid crisis, and massive political instability

On a rainy day in 2015, David Kessler was driving in Los Angeles when he got a call from a number he didn’t recognize. “We have the vice president on the line,” a voice informed him.

Vice President Joe Biden? Kessler thought.

He immediately pulled over.

As he drove onto the shoulder, another voice came booming through the phone: “Hi, David! It’s Joe! How are you?”

There was a camaraderie in his tone, Kessler would later recall, as if the two had known each other for years, despite having never met.

Kessler is one of the world’s foremost authorities on grief, and he’s published five books on death and bereavement, including “Finding Meaning.” The vice president had been particularly affected by Kessler’s work on finding meaning after loss. As Kessler recalled, Biden felt obligated to abide by his mother’s advice: When you appreciate someone or their work, you thank them.

A few months earlier, Biden had lost his older son, Beau, the former attorney general of Delaware, to brain cancer. He was 46 years old. It was Biden’s third deep wound from grief. In 1972, Biden’s wife, Neilia Hunter, and their baby daughter, Naomi, died in a car accident while out Christmas shopping. Biden, then a senator-elect, was 30.

Kessler listened to the 72-year-old vice president describe his own role as grief counselor — someone who helps others through their grief — and how that has helped him find meaning.

“He is not afraid to connect with the pain,” Kessler told Insider.

But things had been getting harder recently, Biden said. Just a few months after Beau died, he went to Charleston, South Carolina, to comfort survivors and loved ones of the nine Black churchgoers killed in the Emanuel AME Church shooting. The decision followed the dozens of eulogies he’d given for family friends and public figures over the years — a habit that’s earned Biden a reputation of being one of the best eulogizers on Capitol Hill.

“He talked about how being in deep grief, it’s even harder to show up,” Kessler recalled. “But he was undaunted, and it would never have entered his mind not to do it. I think empathy is his secret power.”

Biden checks a lot of boxes as your typical politician. The 78-year-old has a receding hairline, marked crow’s-feet, white skin, and whiter hair. He stands at 6 feet and flashes a bright toothy smile. Politically, he’s viewed as a moderate Democrat.

But a closer look into the life of the president-elect reveals a man deeply shaped by sadness, comfortable with vulnerability, and in possession of a unique ability to connect with others. And yet, over his nearly five decades in politics, he’s faced controversy, scandals, and gaffes, some of which have led to national discussions over Biden’s fit for certain offices.

Insider spoke with several former colleagues of Biden, including former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid and official White House photographer David Lienemann, in addition to leadership experts like the “Grit” author and psychologist Angela Duckworth and the writer Evan Osnos, to get a close-up look at what they say are the strengths and weaknesses of America’s new leader.

What emerges is a complex portrait of an imperfect leader.

Colleagues widely agree that Biden’s warmth and compassion set him apart from other politicians, yet his default to intimacy and his sometimes lack of awareness of boundaries have been problematic. Several women have accused Biden of inappropriate, nonconsensual touching, to which he responded that he would be more “mindful” moving forward. One woman has accused him of sexual harassment and assault, which Biden denies.

He’s known on Capitol Hill as a politician who gets deals made and legislation passed, in large part because of his ability to create compromise. Yet his penchant for the middle ground fuels critics’ argument that he isn’t progressive enough. (The Biden administration did not comment for this article.)

Today, Wednesday January 20th, Biden will begin to lead a country struggling to grieve the many who’ve died from the coronavirus pandemic and the still raging, if overshadowed, opioid crisis. On an even larger scale, millions of Americans are grieving the loss of a sense of safety, of a once held belief that the nation’s democracy was so strong it was bulletproof, an illusion exposed by January 6th’s violent attempted coup.

That Biden, too, is mourning on a deeply personal level, and is known for his emotional vulnerability, could have a powerful effect on American society, helping to unite a country so strongly divided. Biden may not be America’s savior, but his leadership style could be enough to help a wounded nation start on a path to recovery.

Growing, and tending, his working-class roots

The eldest of four children, Biden was born in the blue-collar city of Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1942. When his father, a used-car salesman, couldn’t find work when the city fell into economic decline, the family moved to Delaware, eventually establishing roots in the gritty suburbs of Wilmington.

He attended an elite all-boys Catholic high school, Archmere Academy, but he had to work on the grounds crew in order to pay for it. The experience made him highly sensitive to the markers of class, dignity, and respect, said Evan Osnos, the author of the biography “Joe Biden: The Life, the Run, and What Matters Now.”

Biden’s mother used to tell him that he was “no better and no worse than anyone else.”

These working-class roots would inform Biden’s broader view on politics, said Lienemann, the White House photographer for Biden all eight years during the Obama-Biden administrations and author of “Biden: The Obama Years and the Battle for the Soul of America.” Beyond snapping candids of Biden chatting with heads of state, Lienemann spent ample time alongside Biden in his office as he worked on policy.

He recalled that Biden would frequently pose questions like: “If you couldn’t write policy and relate it to people in a working-class neighborhood, then really what was the point of the policy? And what was the point of giving the speech?”

Biden graduated from the University of Delaware and Syracuse University’s College of Law. After working as a lawyer for a few years, and winning his election to the New Castle County Council, in 1970, Biden set his sights on the nation’s capital.

But Washington, DC, was a club he didn’t quite fit into.

“He didn’t go to an Ivy League school,” Osnos said. “He didn’t feel 100% at home among the Rhodes Scholars and others in Washington who were flexing their credentials.”

Voters often classify Biden as a moderate in policy. His $5.4 trillion proposed government spending budget over the next decade is a fraction of those of his 2020 Democratic-primary rivals, which ranged from $30 trillion to $50 trillion. And over the years Biden has often fallen closer to the center than to the left on several issues, such as advocating for cuts to Social Security spending throughout his career in the Senate.

But his connections to his roots have also been reflected in some of his legislative efforts. Over the course of his career in the Senate, Biden consistently voted for minimum-wage increases. And in 2007 he voted in favor of the Employee Free Choice Act, which would have protected the rights of workers to unionize.

“Working-class, middle-class people built this country,” he said in a December speech about his plan for COVID-19 recovery efforts. “We can build a new American economy that works for all Americans. Not just some — all.”

Getting accustomed to perseverance

Adversity began early for Biden. Ever since he could talk, he had a speech impediment, a stutter, and he was bullied for it as a teen. Classmates assigned him nicknames like “Bu-bu-bu-Biden,” “Joe Impedimenta,” or “Dash,” with a few of his peers likening his speech to Morse code. Some would bully him physically for it.

To correct his stutter, his parents took him to a speech pathologist, but it didn’t help. Instead he took to reciting poetry, working hours upon hours to get every last line right from his favorite authors, including Yeats and Emerson.

He began standing up to his bullies.

“Get up!” his father would say after hearing about his son’s struggles at school. The stern direction would echo through Biden’s head for years later, shaping him as a person.

Researchers who study bullying say its effects can last well into adulthood. It makes a person feel more vulnerable, and a person’s character can be deeply shaped by how they respond to that vulnerability.

“One could come out of adversity and become callous,” Angela Duckworth, a psychology professor at the University of Pennsylvania and CEO of the Character Lab, told Insider. “But what’s so admirable to me about Biden is that he exudes authentic compassion, which I think has been strengthened, as opposed to weakened, by his personal story.”

It seems to have been the case with Biden. He’s become a vocal advocate for those who face the same struggles with speech impediments.

“You know, stuttering, when you think about it, is the only handicap that people still laugh about,” he said in a 2020 CNN town hall, one of several speeches in which he’s mentioned stuttering.

He’s encouraged others living with a disability not to let it define them as a person, and at the same time to embrace what makes them unique.

“It’s a funny thing to say, but even if I could, I wouldn’t wish away the darkest days of the stutter,” Biden wrote in his 2008 autobiography, “Promises to Keep.” “Carrying it strengthened me and, I hoped, made me a better person.”

In 1972, he ran for senator and won, ousting Republican incumbent J. Caleb Boggs by fewer than 3,500 votes. Then, just weeks after the triumph, tragedy struck. On December 18, Biden was working on hiring his staff when the phone in his office rang. He picked it up. It was a first responder.

His wife, Neilia Hunter, and their 13-month-old daughter, Naomi, had died in a car accident. His two boys, Hunter and Beau, were badly injured. Years later, speaking to a group of military families mourning their children who died while serving their country, Biden said the experience of losing them made him understand why someone would consider suicide.

Still, buoyed by the encouragement of senior senators, he was sworn in, the youngest person ever to occupy such a position at that time. The ceremony took place in the hospital where Hunter and Beau were being treated, at the boys’ bedside.

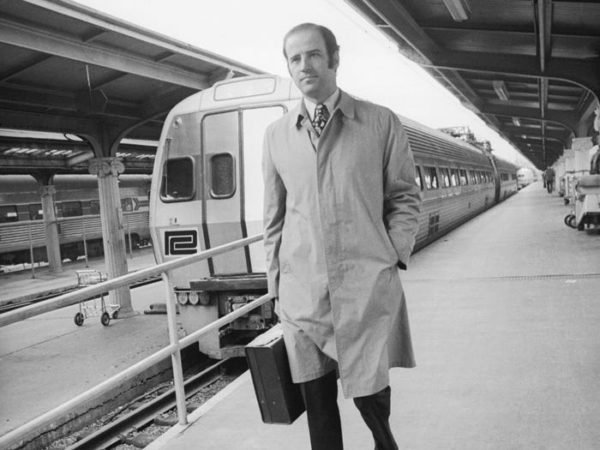

From that point on, Biden prioritized family over everything. He made the 90-minute commute from Wilmington to DC every day so that he could be home to tuck his boys in bed at night. (It’s how he would rack up over 2 million miles on Amtrak, or so legend has it, giving him the nickname “Amtrak Joe.”)

Learning to find his voice

Though Biden would learn to manage his stutter in his 20s, he struggled to find his voice politically. Early on in his congressional career, he gave a long, impassioned speech about oil wells. When he finished, an opponent, Sen. Russell Long, from Louisiana — apparently wary of Biden’s credibility — asked him a pointed question.

“Senator Biden, have you ever seen a stripper well?” Long asked, referring to a kind of well that produces little oil or gas. Biden was mortified. He hadn’t. And now others knew he hadn’t.

From then on, over-preparation and listening became Biden’s sharpest tools. He’d do his homework and consult the experts closest to him, Osnos wrote in “Joe Biden.”

“He had to learn in that period that there are limits to the gift of gab, and he had to back it up with knowledge,” Osnos said. “He became a little more prudent” — with a few bumps along the way.

In 1987, Biden launched a presidential bid that ultimately crumbled after he was accused of lifting quotes without attribution from a British Labour Party politician, and later from Robert Kennedy. Then Newsweek found C-SPAN footage in which Biden boasted about his academic accomplishments, saying he “ended up in the top half of my class.” In fact he ranked 76th out of 85. Soon after, he said he mistakenly plagiarized in law school, adding that it was not “malevolent.” The campaign fell apart.

Later, when asked about the matter, Biden apologized and said his “arrogance” was to blame.

“He was a man in a hurry,” Osnos said. “And I think if you’d encountered him in that period, you would have come away with the impression that he was a little callow, that he was more interested in the office perhaps than in the content of the policy.”

All that changed in February 1988, when he collapsed on the floor of a hotel room in Rochester, New York. He’d experienced a brain aneurysm and nearly died. He was flown to Walter Reed hospital, where he stayed, out of commission, for several months.

Biden said that the experience forced him to slow down and shaped him into the kind of man he wanted to be.

“I was no less committed or passionate,” he wrote in his 2008 autobiography, “but I no longer felt I had to win every moment to succeed.”

Becoming a man known for compromise

In the Senate, Biden developed a reputation for connecting with a variety of politicians, regardless of their political party.

Given the political climate today, his ability to push for compromise from all ends of the spectrum is a major strength, said Rosabeth Kanter, a leadership expert and professor of business administration at Harvard Business School.

“Collaboration with multiple stakeholders is essential to lead change, even radical change,” Kanter told Insider. “Change starts with allies who might not agree among themselves.”

Orrin Hatch, the former senator, once remarked, “Joe’s innate ability to befriend anyone — and I mean anyone, including his fiercest political opponents — was critical to his success as a legislator.”

Former Sen. Harry Reid said that when he would butt heads with Republicans, he’d turn to Biden for help.

“Senator Mitch McConnell and I worked together for decades,” Reid said. “He was the whip when I was the whip, we were both leaders, but sometimes we would talk past each other.” He said he knew Biden could be counted on to be one of the best shots of coming to some sort of agreement.

“Here’s the one thing about Joe Biden: Joe Biden is a person who understands the word ‘compromise.’ And compromise is how you get legislation done,” Reid added.

McConnell once said that in his office “Get Joe on the line!” was code for it’s time to “get serious” about passing legislation.

Biden would become the chairman of both the Senate Judiciary Committee and the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, and a driving force behind a series of important legislation, most notably the Violence Against Women Act of 1994.

It provided $1.6 billion toward investigation and prosecution of violent crimes against women, established the Office on Violence Against Women within the Department of Justice, and created a hotline that’s helped millions of women.

But that period of progress also marked the onset of some of Biden’s greatest controversies.

There was Biden’s overseeing of the Supreme Court nomination hearing of Clarence Thomas. In 1991, a law professor named Anita Hill spoke before an all-white, all-male Senate Judiciary Committee about sexual harassment she said she endured from Thomas.

The senators asked Hill questions that many now say were invasive, uncomfortable, and unfair. Biden did not allow testimony from three other women who offered their own stories about Thomas.

In April 2019, The New York Times reported that Biden had called Hill to apologize. According to Hill, what he said to her did not constitute an apology.

“I cannot be satisfied by simply saying, ‘I’m sorry for what happened to you,'” Hill, now a professor at Brandeis University, said.

Osnos commented on the infamous hearing, saying that Biden thought his motives were misdirected in the interest of trying to ensure the first African American nominated to the Supreme Court was given a fair hearing. “But in the process, of course, he made a terrible mistake,” the biographer said.

An ability to listen and connect with others

If you ask his staff what Biden’s biggest flaw is, they’ll tell you it’s his inability to stop talking to people. Both as a senator and as Obama’s vice president, Biden was known to talk and talk with people, pushing back his schedule with every conversation.

After a televised town hall or some other event would end and all the guests would leave, the cameras put in their cases and the lights switched off, Biden would often still be in the middle of the room talking to the last few remaining people, trying to strike an emotional connection, the photographer David Lienemann said.

“There was always sort of this tug and pull because he really wanted to stay,” Lienemann said. “His staff was always kind of trying to get him out the door and on to the next thing.”

Bettinger-Lopez, who worked with Biden on efforts to reduce sexual violence, attended on-campus rallies with the vice president to raise awareness of sexual assault.

“He would have sometimes dozens of survivors crying on his shoulder after these rallies,” she said. “They’d be telling their stories, and he would stay and listen to each and every one of them.”

Biden’s desire to connect with others traces its roots to the earliest points in his career.

A grieving leader

Saturday, June 6, 2015, was a warm summer day in Wilmington. Biden, dressed in a navy-blue suit and tie and dark aviators, stood outside the St. Anthony of Padua Roman Catholic Church, looking on as servicemen lifted a coffin out of a hearse.

Biden watched as an American flag was draped over the casket. At one point he raised his hand to his heart. Scottish bagpipes sounded a song of mourning.

A few months later, Biden made a phone call. He’d been reading books on grief and wanted to speak to one of the authors, who, it turned out, was driving when Biden called. By the end of the call with David Kessler, however, Kessler wasn’t as much comforting Biden over the loss of his son Beau as much as it was Biden doing the comforting of Kessler, who had lost his mother.

“I didn’t have to teach him that premise that I often have to teach others: that life after loss can be meaningful,” Kessler said. “That’s the whole sixth stage of grief, it’s finding meaning. Meaning and purpose, we talked about, are clearly important to him.”

On “The Colbert Report” in 2017, Biden talked about his experience with grief and his book “Promise Me, Dad.”

Biden recounted the evening he made a promise to Beau that he would continue, and would keep living with a sense of purpose after his son’s death. “Promise me, Dad, you’ll be OK,” Beau had said. Biden swore he would. (He didn’t run for president in 2016, citing his personal anguish.)

When Colbert asked Biden why he wrote the book, he said, “I wanted to give people hope, that through purpose you can find your way through grief.”

Five and a half years later, it’s clear Biden is still mourning. At his presidential victory speech in November, fireworks lit up the night sky as Coldplay’s “Sky Full of Stars” blasted from the speakers. The song was later revealed to be Beau’s favorite. Coldplay’s Chris Martin had played at his funeral.

“This is the time to heal in America,” Biden said, looking out at the crowd. The following day, as millions of Americans took to the streets to celebrate Biden’s win, the president-elect visited Beau’s gravesite.

Moving forward

Americans are getting a rare glimpse at a leader publicly acknowledging the role dying and mourning play in our lives. And amid the pandemic and the opioid epidemic, it couldn’t come at a more important time.

By continuing to share his story, Biden has the potential to help the nation address its grief, said Deborah Carr, a professor and chair of the sociology department at Boston University.

“He really has this opportunity to say to all people, but to men especially, ‘It’s OK to grieve. It’s OK to grieve publicly. It’s OK to grieve not on a set timetable,'” she previously told Insider.

His experience in the Senate, specifically his ability to forge compromise, will also help the country, former Sen. Reid said.

“Joe Biden is one of the better equipped, experienced people to ever become president of the United States,” he added. “He’s got varied experience as a legislator and he’s got eight years of experience as an administrator as part of the administration.”

To be sure, the incoming president is a flawed human being with a controversial and complicated past. But Biden’s leadership style, characterized by vulnerability, openness, and compromise — not to mention his Democratic-controlled Congress — could help him steer the country toward economic and political growth. He recently unveiled a $1.9 trillion economic rescue package, which calls for $1,400 per person in stimulus checks and $350 billion in assistance for state and local governments.

In his national address on January 6, the day of the attempted coup at the Capitol, Biden called for unity.

“The work of the moment and the work of the next four years must be the restoration of democracy — of decency, honor, respect, the rule of law, just plain, simple decency,” he said.

“There’s never been anything we can’t do when we do it together.”