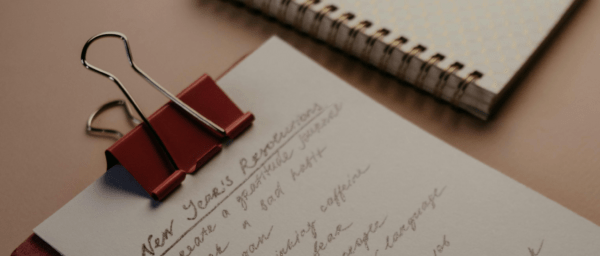

Indifference About Foreign Languages is Costing Us Billions

The UK’s lack of foreign language skills is costing us up to £48 billion a year. But in spite of this huge cost to our economy, the UK is still regarded as “the worst country in Europe at learning other languages”. So why is the UK still indifferent about learning foreign languages?

“Everyone speaks english anyway”

In 2014, research showed that 39% of young people were put off learning another language because they thought “most people speak English”, while 14% thought that “most other languages are not useful”.

While it is true that English is the most widely spoken language in the world, the fact remains that the world’s strongest economies are not all primarily English speakers. In fact, depending on whether or not GDP (gross domestic product) or GDP based on PPP (purchasing-power-parity) is taken into account, the strongest economy in the world is either China or the USA.

Chinese is not far behind English in terms of the number of speakers worldwide, and according to business translation experts London Translations, “if (English’s) legitimacy in Europe were to fall in the wake of Brexit, that could clear a path for German and French to take the top spot”, as Germany and France are two of the strongest economies in the EU. So if the UK is to keep up with countries which have better foreign languages skills than ours as the global marketplace shifts, then the UK might need to buck up it’s language learning fast.

Education budget cuts

Secondary schools might be facing some of the steepest funding cuts since the 1970s, while the number of those taking a foreign language at A level is dropping. In fact, as of this year less than 1 in 10 of students who take a foreign language at GCSE are carrying it on to A Level.

Teachers are going on record saying that it is largely due to a lack of adequate funding, which makes it difficult for teachers to run smaller foreign language classes. In fact, The Association of Colleges, on its further education job platform has warned that “if these cuts continue, over 190,000 places in further education could be lost”.

The government responded to these foreign language funding allegations by arguing that they are encouraging pupils to take foreign languages through the new English Baccalaureate performance measure at GCSE level.

However, as The Telegraph have pointed out, this scheme bears a remarkable resemblance to the curriculum of 100 years ago. In their words: “It seems ludicrous that we are employing the same strategy in 2016 to increase fluency in foreign languages as we did over a century ago.”

We voted for it

According to The Guardian, “Brexit threatens a retreat to a narrow, monoglot world view and rejection of the expansionist inspiration that has come from closer integration within the EU”.

Indeed, by voting for Brexit, the people of the UK have agreed to the possible loss of EU funding for both the UK’s translated literature industry and the Erasmus scheme, through which hundreds of thousands of students have so far had the chance to live and study abroad. The Erasmus scheme alone was due to inject 1 million euros into the UK economy over 7 years.

And the European Parliament is set to debate on whether or not they are to provide all 18-year-olds living in the EU with a free interrail pass; in an effort to give them “a sense of belonging.” With Theresa May stating that she wants to invoke article 50 before March of next year, it seems that the youth of the UK will also miss out on an experience which is not only enriching, but which also naturally promotes foreign language learning.