How Has the Selfie Redefined Portraiture?

When Kim Kardashian released her photography collection Selfish in 2015, it was welcomed by critics for ushering in a new form of photojournalism. Many treated it as the next big thing in self-portraiture—a new form of autobiography. The New York Times wondered whether we should look to her as someone “with much to teach us about mastering our own selfish lives”.

But the Guardian countered, claiming it was a slap in the face for anyone who ever pointed a camera in hope of being the new Henri Cartier-Bresson. Considering the ease with which we can all capture that image ourselves, is the selfie the nail in coffin for portraiture? Or how might it be redefined?

The selfie isn’t quite putting portrait artists out of a job

Long before the selfie—even before the camera—was invented, portrait artists were commissioned to create images of rich and influential persons that captured and preserved their identity and presence. Portraits have traditionally been flattering, and painters who refused to flatter, such as William Hogarth, often found their work rejected. Over time, the distinct figurative and representative styles of portrait artists came to be celebrated in their own right, from Van Gogh to Mary Cassatt, Pablo Picasso to Lucian Freud.

Contemporary artists are once again taking portraiture in new and unexpected directions. JJ Adams, for example, redefines what it means to capture a portrait, superimposing intricately tattooed designs upon his subjects (including David Bowie, Julia Roberts and Jim Morrison) in his defining Tattoo Series. In many ways, his works are a portrait of the artist himself: Adams once worked as an apprentice at a popular tattoo studio with the ambition of becoming a full-time tattooist.

If portrait artists aren’t as objective as they used to be, self-portraits certainly aren’t either. Early examples of artists’ attempts to paint themselves are modest and spasmodic, others are especially scrutinous, and some depict themselves as wild caricatures. Artist Käthe Kollwitz made a self-portrait, Hand at the Forehead, as a birthday present for her husband who, along with their sons, claimed it did not bear any resemblance to the artist at all.

One popular belief is that the sole purpose of self-portraits is to bring us into contact with the artist’s soul. The self portrait for Van Gogh was approached as a thing of fear and dread. Another belief is that the self-portrait enables us to capture our image subjectively—the way we see ourselves.

Is there a difference between selfies and self-portraits?

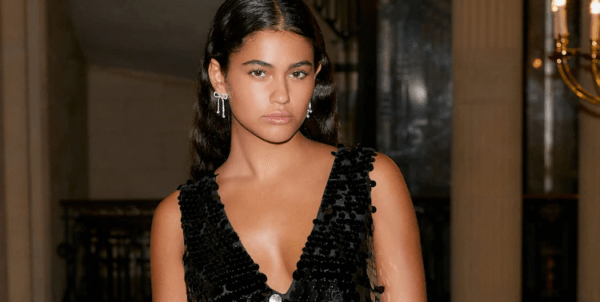

In an attempt to explain the difference between the selfie and the self-portrait, a Getty Museum blog simply suggests, a selfie is a self-portrait taken with a smartphone. The selfie is a form of self-portraiture because the subject is the artist too—he or she captures their own image in the way they want to be seen. Despite protestations that selfies deny and erase a fundamental human self-consciousness, they have much in common with famous self-portraits of old by making the artist an active agent in how their own image will be preserved.

But it’s not just the selfie that’s changing the way we think about portraiture. Artist Tracey Emin recently created her own portrait death mask in order to “transform herself into an object of scrutiny for generations to come”. In doing so, she challenges our perceptions of self-portraiture. It’s common for artists to explore their morality in self-portraits, but death masks have traditionally been cast directly from a corpse; Emin’s death mask, then, is a way for her to reclaim the most definitive form of all portraits for herself.

But selfie culture is not necessarily self-empowering. Selfies are part of our attempt to take back the images of ourselves, but in the process we also give ourselves away. Thanks to their social network dissemination, selfies become decontextualized. Their subjectivity is lost in a sea of internet anonymity.

If selfie culture has encroached on the notion of the self portrait, what does that mean for portraiture as a whole?

Today self-portraiture is once again a healthy and vital discipline in the art world. While many are returning to traditional techniques to address contemporary issues, others are taking wildly nontraditional approaches. In 2000, Colombian artist Juan Pablo Echeverri began going to photo booths and taking shots of himself in different guises. Nan Goldin depicts herself with a vivid black eye, a challenging photograph taken to prevent herself forgetting the damage caused by a boyfriend’s violence.

This new interpretation has much in common with Rembrandt’s series of autobiographical self portraits painted in the years before his death, as well as Frida Kahlo’s enigmatic works. Now, as part of an exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery, artists are even being invited to explore selfies as an art form. Nigel Hurst, the gallery’s CEO said: “In many ways, the selfie represents the epitome of contemporary culture’s transition into a highly digitalised and technologically advanced age.”

But this was not a sentiment shared by historian Simon Schama during a powerful attack on the selfie age. Schama ridiculed the idea that the “quick dumbness” of selfies has anything in common with the true art of portraiture. He explained: “What we love about selfies and phones is that it’s of the moment, but the true object of art is endurance.”

With critics divided, it remains to be seen whether selfie culture will stand the test of time and, indeed, if the phenomena is actually the dawn of a new artistic revolution. For now, the attraction of the selfie as a form of portraiture seems to be about what those images say, and about whom they say it. The selfie, like the self-portrait is all about playing a game with one’s own notion of identity.