A Thousand Words – How Art Embraced Text

The old saying goes that a picture paints a thousand words, but since the mid-twentieth century, contemporary art has been increasingly interested in making use of text. Through the ages, it has served a range of different purposes, from simply telling a narrative story to emphasising key ideas and grabbing viewers’ attention. Coming to the forefront in the era of conceptual art, this drew on the high-impact imagery of the advertising world, and helped to make the complex ideas of many artists’ works easier for people to digest.

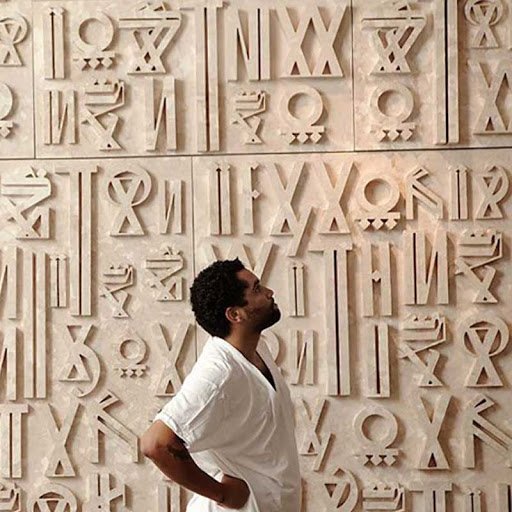

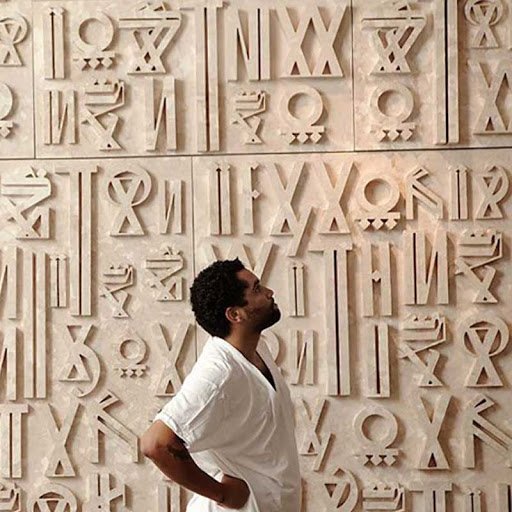

In more recent years, particularly with the rising prominence of street art rooted in graffiti and tagging, text has taken on an even greater significance. Artists like Retna, for example, not only use words in modern English in their work, but “a range of scripts from around the world”, to highlight his own multicultural background and the globalised world in which we live. But how did text-based art originate, and when did it come back into vogue?

The treachery of images – text and surrealism

By the start of the twentieth century and the evolution of movements which would come to be known as modern art, artists were looking for ways to shake up the traditional techniques of creating art. As the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art explains, text was used in the work of early Cubists like Braque and Picasso in an effort to “liberate…painting from its formal properties,” allowing artists to base their work on themes which couldn’t be easily represented by figurative painting.

The likes of the Dadaists also embraced text, most infamously in Rene Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, which deconstructed the notion of figurative art altogether. The painting depicts a pipe, with the phrase “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”) underneath, emphasising that what is on the canvas is merely a picture of a pipe, rather than an actual pipe.

“Whaam!” – text goes art goes pop

By the 1960s, the twin influences of advertising and comic books had a profound impact on the direction of the decade’s art movements. Most notably, works like Roy Lichtenstein’s legendary Whaam! canvases worked to, as the Tate gallery puts it, “conflate…the powerful but so-called ‘low’ mass-produced commercial image with the traditionally venerated medium of large-scale easel painting.”

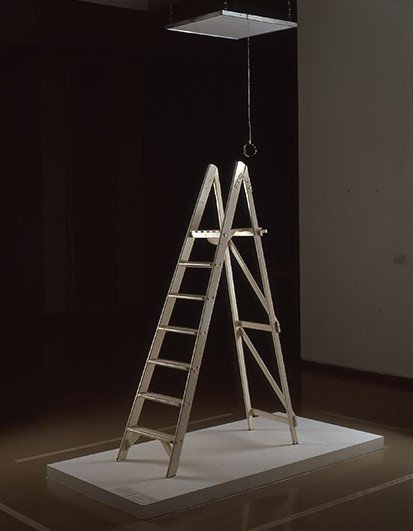

Meanwhile, the Fluxus art movement, who specialised in more performance art-based works, used text to provide instructions to those viewing their highly conceptual pieces. Yoko Ono’s Ceiling Painting/Yes Painting, is a key example of how text can be used in a work of art. The piece consists of a ladder, leading up to a square piece of paper under a metal frame, with a magnifying glass suspended from it — viewers simply climb the ladder, and pick up the magnifying glass to read the single word of text printed on the paper: “Yes”.

Created in what she describes as a “totally difficult situation in [her] life”, Ono’s 1966 piece is arguably best-known for being a key part of the exhibition where she first met her husband John Lennon. Indeed, it was the text itself which actually drew the Beatle to the artist. As Lennon told Rolling Stone editor Jann Wenner in 1970, “It’s a great relief when you get up the ladder and you look through the spyglass and it doesn’t say ‘no’ or ‘fuck you’ or something, it said ‘yes’.”

Leaving the 20th century – tags, signs, and text

Graffiti and street art was arguably the defining movement of late 20th century art, and the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat would combine spray-painted images with crudely-scrawled text to further emphasise his works’ social commentary. However, this was not the only way that words became more widely incorporated into works of fine art.

Again drawing on the common signs of consumerism, artists like Jenny Holzer and Ed Ruscha would not only be defined by their use of text, but even by the way their words were presented. The latter makes use of his own bespoke typeface, while Holzer is renowned for her use of LED banners, spreading reactionary messages (“Abuse of power comes as no surprise”, reads one of her most famous slogans) by co-opting commercial forms of communication.